Curbed – The First Artist Who Moved Into This Soho Loft Building Is Moving Out

DETAILS:

Price: $4.495 million ($5,000 monthly maintenance)

Specs: 4,000 square feet, currently divided into 4 bedrooms, 3 bathrooms, 3 kitchens,

Extras: Roof access, private landing, original exposed brick and steel columns, flexibility to add windows

10-minute walking radius: Fanelli’s, Angelika Film Center & Cafe, Palace Skateboard Apparel

Listed by: Michael Falchiere and Harry Zikos, Oxford Property Group

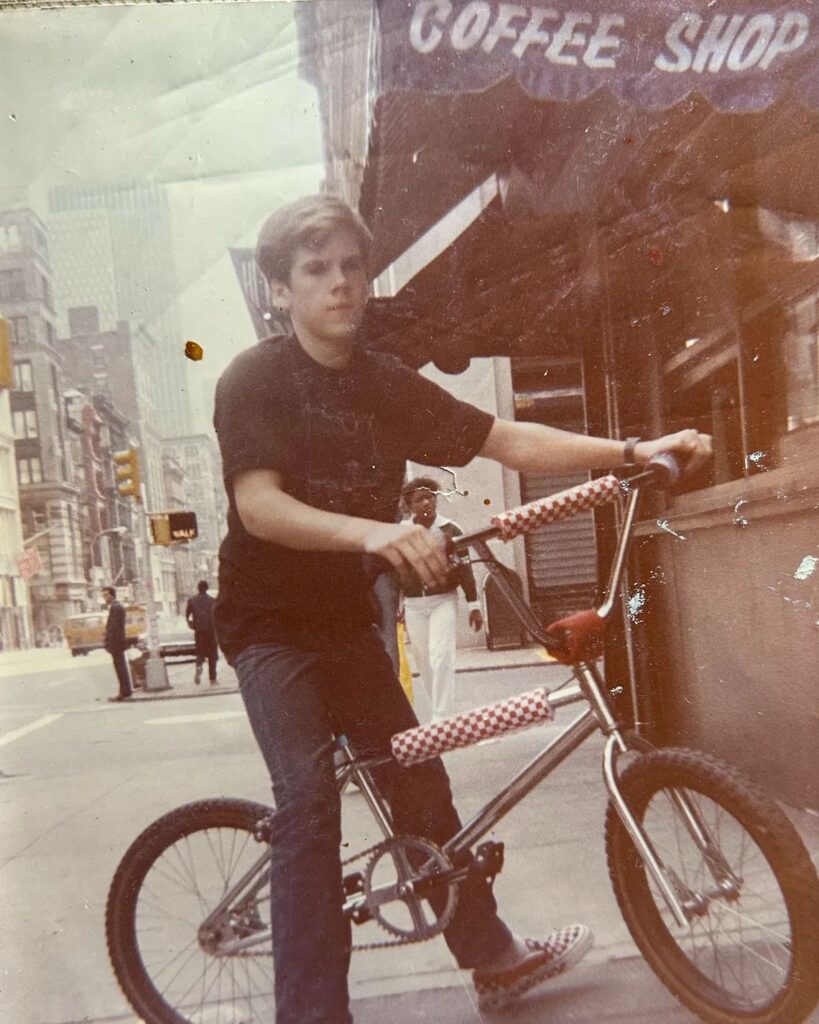

Anyone who stopped by Sal Lindsay’s Soho loft in the evening used to get a warning: Bring enough cigarettes to last because none of the shops nearby stay open. “We used to joke that once the sweatshops closed, nothing went down Broadway but tumbleweeds,” said Lindsay’s son, Chris Bos. “No bodegas, no little delis. There was nothing.” Which is why, when Bos was a teenager, he spent a lot of time in his bedroom, where Lindsay, a single mom, let him build a quarter-pipe for friends to do BMX tricks or skate. Visitors included friends he met at Washington Square Park — a young Vincent Gallo, the legendary skater Harry Jumonji. “The noise didn’t carry,” said Lindsay, who used the front of the 4,000-square-foot apartment as a painting studio. “I never had any idea, anytime, what they were up to.”

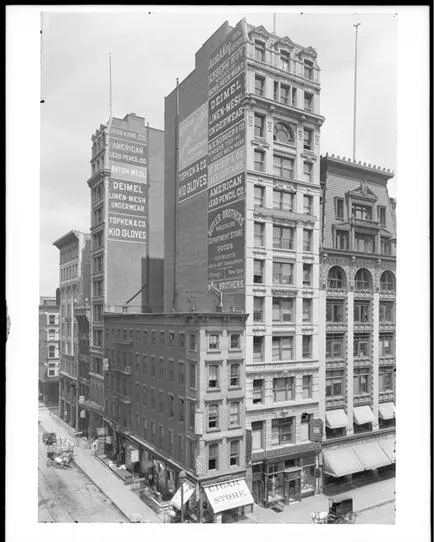

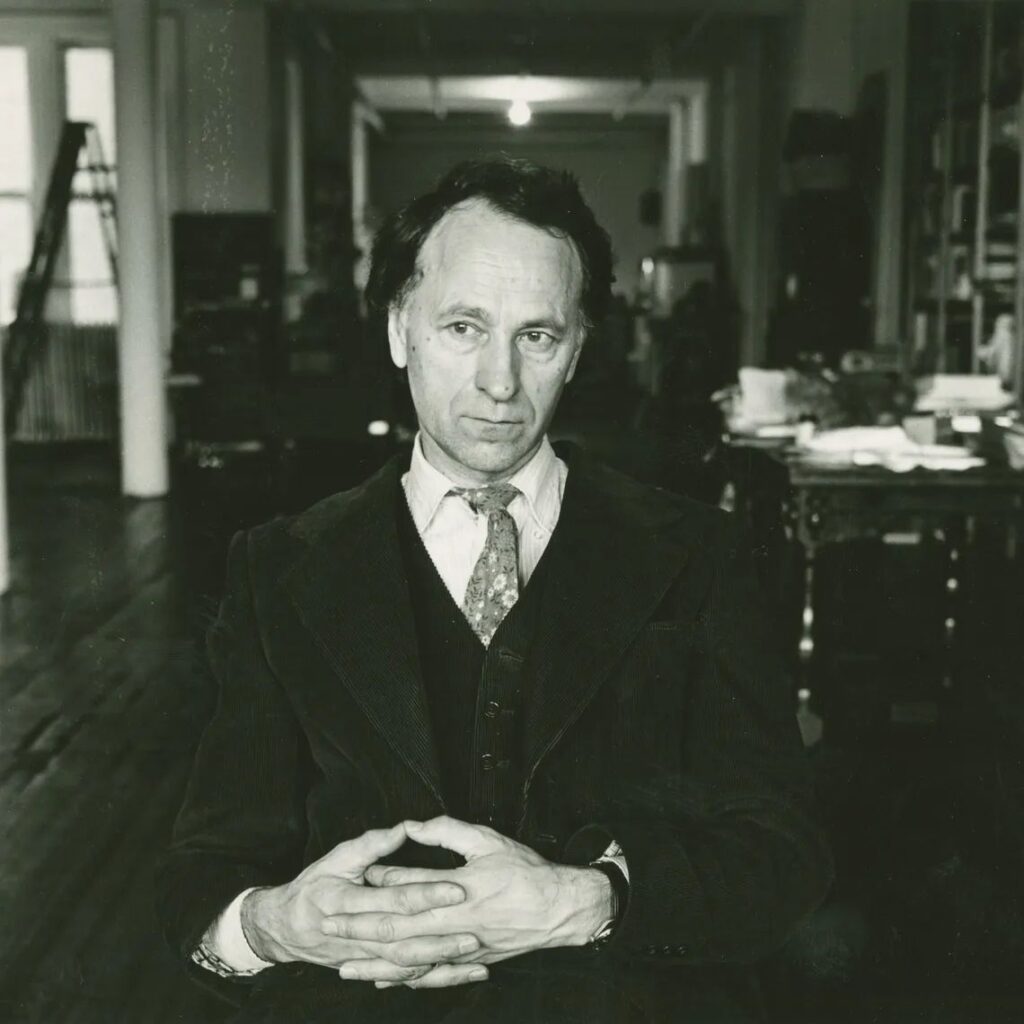

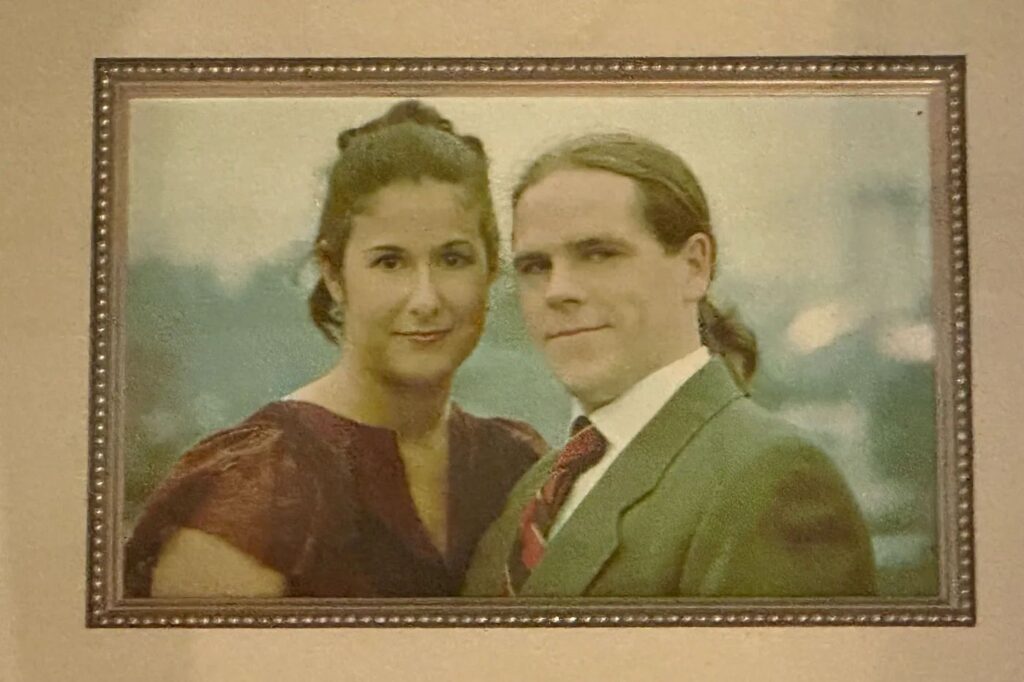

Lindsay, a figurative painter, moved into the apartment at 491 Broadway in 1971. She and her husband, John Bos, a theater director, were the first of what she called the “homesteaders” in the building. They took the top floor, 12, because it was emptying out: A business downstairs had used it for storage and was downsizing, taking out boxes as the new renters put up walls. Over the years, the couple added antique doors and stained glass they had salvaged in Pennsylvania, where they met as students and where Bos had worked leading the Theatre of the Living Arts. Lindsay tiled a bathroom in a sweeping mosaic of a woman in a green dress.

Within a few years, the neighbors downstairs were no longer garment manufacturers and importer-exporters — they were other artists. The building was one of 17 organized by George Maciunas, the so-called Father of Soho whose training as an architect and practice as a Fluxus artist with utopian visions inspired him to take on a real-estate problem: Artists needed cheap space, and there were plenty of industrial buildings downtown. Maciunas got preliminary agreements to buy a handful of buildings and won grants for the first down payments from the J.M. Kaplan Fund and the National Foundation for the Arts, which were “looking for a test case” to challenge the industrial zoning restrictions that hurt artists, according to historian Charles R. Simpson. Then, Maciunas advertised shares in the co-ops to artists for as cheap as $1 a square foot and had enough interest to form waiting lists. He organized applicants into buildings, helped them hire architects and lawyers, and showed them how to build and manage themselves.

491 Broadway was formalized by 1974, at which point Lindsay had been living there for three years already. Maciunas himself moved into the fifth floor, recruiting neighbors from his first artist co-op at 80 Wooster Street, including director Richard Foreman, who set up his Ontological‐Hysteric Theater in his loft — playing to audiences that sat on bleachers, including a Times reviewer who gaped at a cast playing various potatoes. When Foreman moved out, he sold to the artist Camille Billops and the academic James Hatch, who used the space to grow their archive of Black American art history, organizing regular film screenings and inviting the public to watch them conduct interviews with major figures. A collective of Austrian performance artists set up their studio on the 11th floor. The painter Ida Applebroog took space on the eighth, the graphic designer Hans Kung and his family were on nine, and Lindsay recruited her friend — the painter William S. Dutterer — to take Maciunas’s fifth-floor loft when he decided to move upstate, said Dutterer’s widow, Jamie Johnson. “As Bill told it, the minute he arrived at their front door, they gave him a big hug, and before he said a word, they said to him, “The fifth floor is coming up for sale. Why don’t you and Jamie buy it?”

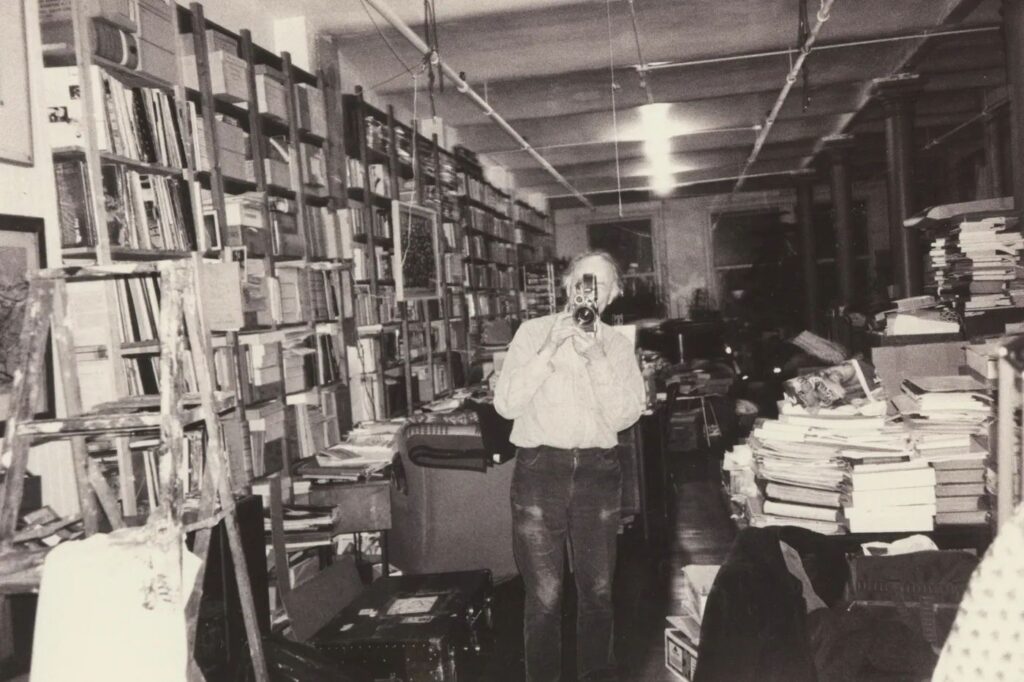

The work of maintaining the 12-story 19th-century industrial building was divided among tenants, and Johnson and Dutterer ended up being in charge of the boiler for 40 years, putting them in “pretty close, sometimes intense, contact” with neighbors, she said. Lindsay and Bos were in charge of clearing snow and salting in winter. The ninth floor took in packages. And the president and treasurer overseeing their work was Hollis Melton, a photographer who moved into the sixth floor with her husband, Jonas Mekas — the filmmaker and Village Voice critic, who also took a commercial space on the second floor, remembered their son, Sebastian Mekas. There, in the 1980s, Mekas kept a library for his Anthology Film Archives and would host $3 viewings under a short-running video program. Meanwhile, his family’s home upstairs showed up in the films Mekas shot — including the five-hour As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, which features his daughter roller-skating through the loft.

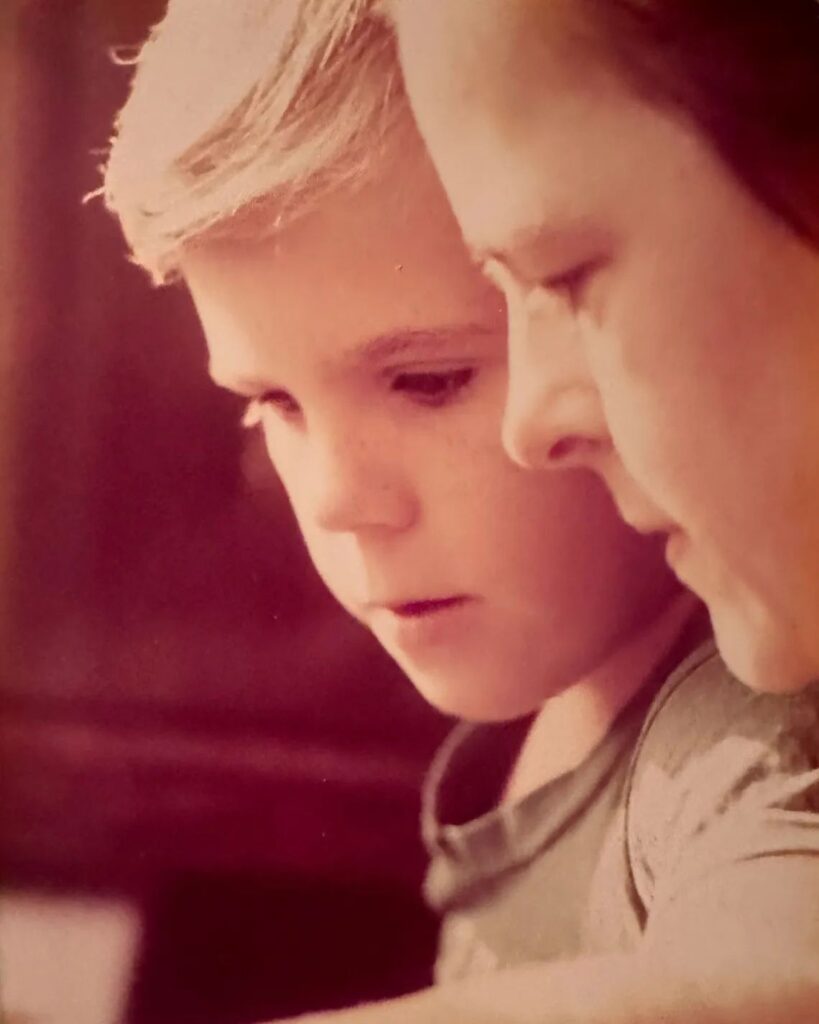

“It was a strange place to grow up as a child,” said Sebastian Mekas, who remembered the surreal neighborhood — treeless, dark — and the oddness of the lofts themselves with high-ceilings that pets found use for. “This one cat, Apache, would somehow get onto the sprinkler pipes. Once it even slipped and was clinging on and had to be rescued with the ladder.”

Jonas Mekas moved to Greenpoint in 2004, Kung sold a few months ago, Dutterer died in 2007, Bilops died in 2019, Hatch died in 2020, and the commercial unit on floor two is no longer a film archive — it’s a marketing agency. Now, Lindsay — the building’s original artist — might, at age 86, be the only “homesteader” left. Still, the space worked well for her, even as her life changed. Around 1980, her husband moved out and, to make ends meet, she carved out space for a renter in the in back — moving her son toward the center of the apartment, in a large, windowed room near the entry where she now has her studio. In 1998, Bos wed his high-school friend Johanna on the roof. She had no second thoughts about moving into his room. “I grew up with everybody on top of each other. So this to me was like, ‘Oh my God — there’s room. There’s space.’”

When they had a second child on the way, they switched with Lindsay and turned her former studio into a full apartment with its own kitchen and bath. When their sons became teenagers, they took over the separate apartment in back. “It gave the boys a sense of independence,” Johanna Bos said. “There’s enough space here that even though we drive each other crazy at times, we have learned to cohabitate.” Her mother-in-law agrees. “There are times where there’ll be days we don’t see each other.”

But the apartment doesn’t make sense for them anymore. They want to be in more of a neighborhood, to have an outside space for their two dogs. And to their brokers, it makes sense to sell: The family’s luck, renting on the top floor because it happened to be emptying out, means they now live in what’s being marketed as a penthouse with room to add windows along a side of the building that isn’t visible from the street. And those views are tremendous: The building is the tallest in an area where their neighbors are four, five, or six stories. From their unit, on the 12th floor, you can look downtown over lower Tribeca and watch traffic snake along the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges. Plus their gradual maintenance means the details here are still intact: exposed brick walls, steel columns. And the bones are rare: Soho buildings on Broadway have bigger floor plates than those on side streets, and the cast-iron structure means there are very few supports. So this is a 4,000-square-foot loft that really someone could do anything with. A blank canvas. “It’s original,” said their agent, Michael Falchiere. “And it’s sort of a one-of-one.”